“After natural talent and appropriate training, an adequate diet is known to be the next most important element for enhancing the training and performance of sports people.”

Williams

C (1996).

The difference between winning and losing can be of the smallest of margins, especially when elite athletes, who are both talented and motivated, compete. It is in these situations, when that extra attention to detail can make all the difference to the overall result.

Diet affects performance, and the foods that are chosen in training and competition will affect how well an athlete trains and competes. In terms of training, a good diet will help support consistent intensive training without the athlete succumbing to illness or injury. Good food choices can also promote adaptations to the training stimulus. It is important for both the coach and the athlete to understand why a good diet is needed.

However, there is no ‘universal diet’ or ‘magic pill’ that will guarantee an athlete’s optimum health/fitness. Every athlete is different and unique and has different physiological make-ups. Thus, there is no single diet that meets the needs of all athletes at all times. Individual needs also change across the time of year and the phase of training that they are in, and athletes must be flexible to accommodate this.

The key nutrient for energy supply is carbohydrate. Carbohydrate-rich foods need to be the main focus of the diet. The more intense the training programme, the more carbohydrates need to be consumed. Athletes must be aware of foods that can help meet their carbohydrate needs and make these a focus of their diet. Breads, cereals, pasta, rice, and grains as well as legumes, fruits, vegetables and dairy products provide carbohydrates.

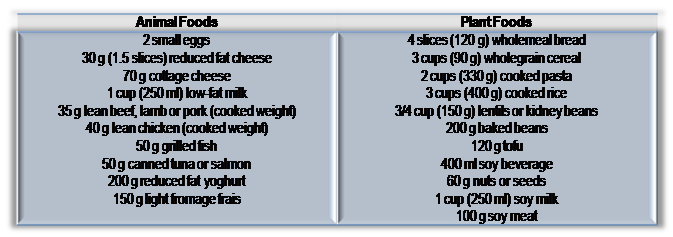

Protein foods are important for building and repairing muscles. People tend to assume that for athletes to obtain enough protein they need to resort to supplementation. However, all athletes (including vegetarians) can meet protein needs by consuming a well-chosen varied diet i.e. largely based on nutrient rich choices such as vegetables, fruits, beans, legumes, grains and animal meats.

Maintaining hydration is another

important factor for performance - before, during and after exercise. Salt replacement is also important when sweat

losses are high, especially in the heat.

FUEL SOURCES

Carbohydrates

The importance of carbohydrate (CHO) to support both training and performance in competition has long been recognised. CHO foods include sugars and starches, which are broken down to form glucose. Glucose is the body’s main source of energy during exercise, especially during intense exercise.

The main form of CHO stored in the body is glycogen, which is found primarily in skeletal muscle and the liver. Muscle glycogen acts as a local fuel for the muscle during exercise, whereas liver glycogen is broken down to glucose and released to maintain glucose levels in the blood.

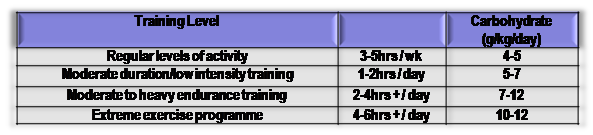

Athletes should include sufficient CHO in their daily diet to support training demands. During training, CHO stores i.e. muscle and liver glycogen are used as fuel by the muscles and these stores must be refilled from CHO in the diet because the body’s CHO stores are small in relation to the daily requirements of an athlete. It is possible to make general recommendations about CHO intake based on an athlete’s size and training regime. However, actual CHO requirements are specific to each individual athlete and should therefore be adjusted according to individual training levels, as well as total energy intake.

Refuelling glycogen storage is a vital part of an athlete’s nutrition. This is the aim of carbohydrate intake before, during & after exercise

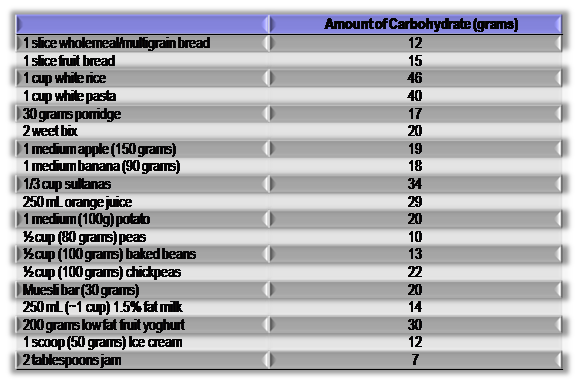

Carbohydrate

Content of Common Foods

The rate of glycogen resynthesis is greatest immediately after exercise. Therefore athletes should try to consume CHO as soon as possible after exercise; especially when recovery time between the next session is short i.e. less than 8 hours.

Athletes should

be encouraged to eat or drink a suitable recovery snack within 15 to 30 minutes

following their session to optimise glycogen resynthesis (suitable recovery

snacks are discussed below). The intake of CHO immediately after prolonged

exercise has shown to result in higher rates of glycogen storage.

Glycaemic Index

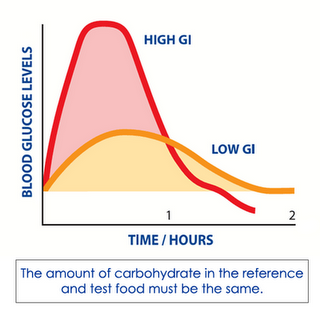

Not all

carbohydrate foods are the same, in fact they behave very differently inside

our bodies. Carbohydrates are broken

down into sugars (glucose) in the stomach and these are absorbed into the blood

stream inside the intestines. Different carbohydrates

are broken down at different rates, so their sugars appear in the blood stream

at various rates and duration.

Glycaemic index (GI) describes this difference by

ranking carbohydrates according to their effect on blood sugar levels. This

ranking is on a scale from 0-100; 100 being the effect of glucose itself. Foods

are termed high, moderate, or low GI depending on their rank.

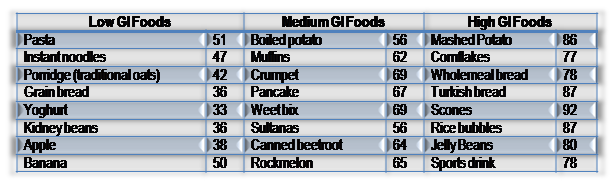

High GI (>70) carbohydrates are absorbed at a fast rate. They cause blood glucose levels to increase rapidly, reaching a very high peak, but leave the blood stream much quicker.

Moderate GI (55-70) carbohydrates have an absorption rate, peak, and duration between both high and low GI.

Low GI (<55) carbohydrates are absorbed at a much slower rate. They cause blood glucose levels to rise but to a much lower peak which is maintained for an extended period of time.

GI content of foods can be used to tailor nutritional strategies. For example in long, endurance events low – medium GI meals prior to the event may help achieve a slow, sustained energy release. Low GI foods are generally recommended in weight loss programmes.

The higher glycaemic index foods may replenish glycogen stores at a faster rate. Low fibre, high GI fluids and foods are best used during training and between races in competition. When there is less than 8 hours between sessions it is recommended that a portion of CHO consumed should have a high glycaemic index (GI), e.g. sports drinks, potatoes, white/brown bread, easy cook rice, low fibre cereals, etc. However, it is still most important to encourage adequate CHO intake suitable for fuelling and recovery as a priority over GI content.

Glycaemic Index of Common Foods

Fat

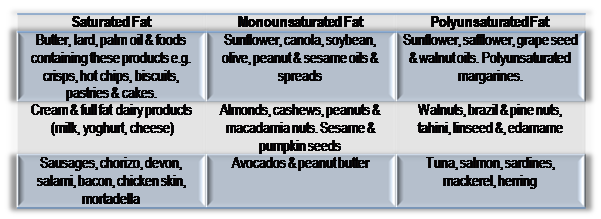

Fat is an important dietary component and is necessary as it provides both energy and the fat-soluble vitamins – A, D, E and K. It also comes in 3 forms: saturated (found in animal products), polyunsaturated (found in vegetable oils) and monounsaturated fat (found in olive oil, avocados & nuts).

Fat is used as a fuel source as well as CHO during exercise. Compared to CHOs, the body has a much larger storage of fat. Even the leanest athlete will have a plentiful supply available to provide energy for very prolonged periods of exercise, so there should be no need to make a special attempt to increase fat stores through food being consumed. Endurance training can increase the body’s ability to store fat in the muscle and increase the ability at which it can use fat as a fuel source. However, the best way to optimise/burn/lose fat is through training and a balanced diet.

It is generally advised to limit the amount of saturated fat in the diet, as it is associated with high cholesterol and an increased risk of heart disease. Conversely, unsaturated fats such as those found in oily fish, nuts and seed oils are associated with lower levels of heart disease.

Fats for

Performance

Essential fatty acids (EFAs) are associated with enhancing thermogenesis (the burning of excess fat to produce heat), thereby assisting the body in losing weight. Furthermore EFA’s are also associated with immunity and anti-inflammatory benefits. Intense exercise programmes induce a reduction of immune cell function; it is proposed that the intake of essential polyunsaturated fats can aid in counteracting this.

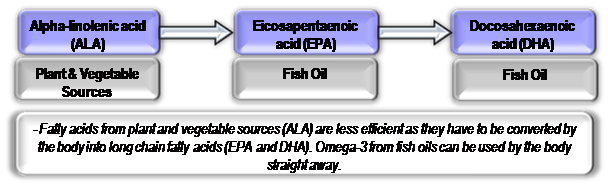

Omega-3

is the name given to a family of polyunsaturated fatty acids that can only be

obtained from the diet. There are different types of omega-3 fatty acids but

the most effective are the long chain fatty acids (EPA and DHA) as they can be

used readily by the body.

Distinguishing foods high in fat content

Protein

Proteins are vital to basic cellular and body functions, including cellular regeneration and repair, manufacture of new muscle and tissue and the repair of old muscle tissue, hormone and enzyme production (which regulate metabolism and other body functions) fluid balance, and the provision of energy.

The component

parts of protein (amino acids) enter the body’s free amino acid pool (body

fluids and tissues) from ingested protein foods, and/or as dispensable

(nonessential) amino acids synthesised by carbon compounds (carbohydrates and

fat) and ammonia. Body proteins are

continually being broken down and replaced by protein, synthesized from amino

acids available in the free pool. However, if dietary protein intake is less

than adequate there are insufficient amino acids entering the free pool to

maintain a rate of protein synthesis to counteract protein degradation. This

can lead to losses in muscle size and strength thus inhibiting performance.

Research

suggests that athletes involved in heavy training programmes may have increased

daily protein needs up to 1.2 – 1.7 g/kg/body weight, compared to the

recommended intake of 0.8 g/kg/body weight for a sedentary person.

Example of food sources

containing 10 grams of protein

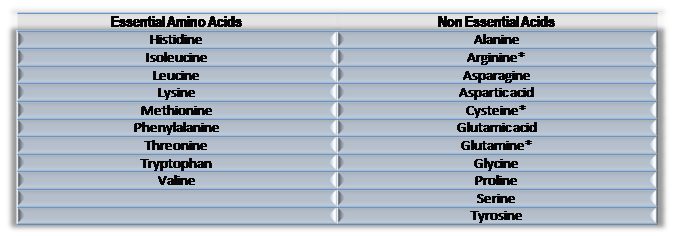

The building blocks of human proteins are twenty amino acids that may be consumed from both plant and animal sources. Nine of these amino acids are considered to be essential because their carbon skeletons cannot be synthesized by human enzymes. The remaining "nonessential" amino acids can be synthesized endogenously with transfer of amino groups to carbon compounds that are formed as intermediates of glucose (glucogenic amino acids) and lipid (ketogenic amino acids) metabolism.

*During periods of intense training or catabolic stress these

amino acids may be considered conditionally essential.

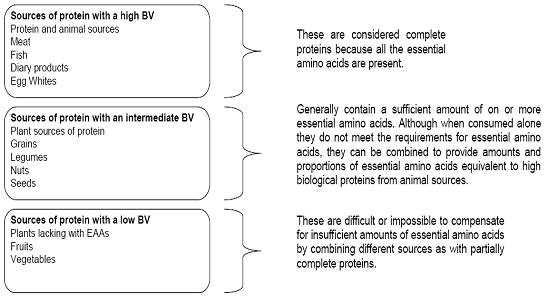

Biological Value

Biological value (BV) is a measure of the proportion of absorbed protein from a food which provides essential amino acids for cellular and bodily functions. If any one of the essential amino acids is not available in sufficient amounts or is present in excessive amounts relative to other essential amino acids, protein synthesis will be not be supported, thus, inhibiting recovery.

Protein is heavily marketed to athletes. Exceeding protein requirements does not give athletes any additional benefits. The concern with excess protein intake is that it may come at a cost to carbohydrate intake which would be detrimental to performance.

Large intakes of protein increases calcium excretion in the body and long term effects of excessive protein intake are as yet unknown. Consumption of protein around exercise (see post exercise snacking, below) is an important part of adaptation to exercise. Consuming protein around exercise should be a priority yet requirements should not be exceeded.

Those who may be at risk of inadequate protein intake include fussy eaters, restrictive eaters (those on diets, limited food supply) or those on poorly designed vegetarian diets.

10.3. ENERGY SYSTEMS

The ATP-CP System

The ATP-CP system provides enough energy for a 5 or 6 second sprint or other rapid muscle contraction such as lifting weights. Creatine Phosphate (CP) is a high-energy molecule that can deliver its energy to manufacture ATP very quickly. A resting muscle has about 4 times more CP than ATP. During muscle contraction, the CP transfers its energy to ATP production, but the reserves are drained quite quickly. CP in the muscles is re-made during the next rest period between sprints. No oxygen is required for this system to work, so an athlete does not need to inhale air during a very short sprint. It is called anaerobic exercise (‘without oxygen’) because no oxygen is required.

Glycolytic System

The glycolytic system is most important for high-power efforts that last up to two minutes. When CP levels are low, the muscles turn to glucose for rapid production of ATP, again with little requirement for oxygen. This anaerobic system generates only 2 ATP molecules from each glucose molecule.

Unfortunately,

lactic acid is a by-product of the glycolytic system and too much lactic acid

will cause muscle fatigue. The muscle

avoids acid fatigue by switching to a third system that requires oxygen, the

aerobic system. As exercise intensity increases,

the body relies more on the glycolytic system fuelled by glucose. When the intensity is lower (e.g. walking,

jogging, easy swim speed), the body prefers the aerobic system that uses both

fat and glucose as muscle fuel.

Aerobic System

The aerobic system requires plenty of oxygen to work efficiently. This system is most important in any exercise that lasts longer than 2 minutes. It is also known as oxidative phosphorylation and uses both glucose and fat as a fuel source. All this takes part in the mitochondria, which are abundant in muscle and the cardiac cells of the heart.

The inhaled oxygen helps the muscles produce a further 34 ATP molecules from 1 glucose molecule, making a total of 36 ATPs, compared to only 2 without oxygen. Glucose is the most efficient fuel as it produces more ATP with each breath than fat or protein. CHO is the main source of glucose in the diet.

However,

body stores of glucose are limited compared to body stores of fat. Endurance training helps muscles to use fat

more efficiently as a fuel, thereby making fewer demands on glucose and thus

improving endurance. Amino acids from

proteins are sometimes used as a fuel, mainly near the end of endurance sports

when glucose is low.

All 3 energy systems operate at

the same time, but their relative contributions change with the intensity and

duration of the sport.

PRACTICAL NUTRITON & SWIMMING

Food does not make an athlete fast.

Quality training makes an athlete swim fast – but part of quality training is good nutrition.

Believe it or not, an athlete does not get faster during training. The coach may see their athletes’ times improving but adaptation to training actually takes place when their body is at rest. Training is simply the stimulus that causes this to happen.

Athletes

inevitably find training hard on occasions and of course, that is the

intention! The body then responds by

becoming more efficient – aerobically and anaerobically so that next time they

can do the set the same, if not better.

However, it is during an athlete’s time off between sessions and how

they refuel that will determine how well their bodies will adapt to their

training demands. Therefore the correct

and proper fuels are vital.

CHO

and Fat as fuels:

During

exercise, the body burns a mixture of fat and glycogen but glycogen is the fuel

that will run out the quickest. It is

therefore, referred to as a rate

limiting fuel. The glycogen

molecules release glucose units, as glucose is the preferred fuel, especially

as exercise intensity increases, which is why CHOs are so important in

swimming. During high-intensity

exercise, glycogen is used at a very fast rate and may become depleted after 30

to 45 minutes, yet it may last for 180 minutes in a brisk walk/ swim speed.

At

lower intensities (recovery sessions), both body fat and glycogen are used as

fuel. As already stated, everyone

carries a certain amount of fat on their body and this amount can equate to

60,000 calories even for a slim person.

Therefore, glycogen as previously stated, is the limiting fuel, simply

because there is a limit to how much can be stored in the body. It is, thus, important to replace these

stores as soon as possible after exercise has been carried out, ideally in the

first 30 minutes afterwards (see suitable kit bag snacks).

Glycogen level Maintenance

Muscle

glycogen levels vary among people i.e. a trained athlete will have more muscle

glycogen than someone carrying out less activity. Fitter athletes aim to keep muscle glycogen

levels as high as possible so they can train effectively for long periods and

recover quickly.

Athletes will

store lots of glycogen in their arms and leg muscles but unfortunately, if leg

muscles run out of glycogen, it is not possible to bring in a supply from the

arms and vice versa. When muscle

glycogen levels hit this ‘low’ and blood glucose levels start to drop, it is

often referred to as ‘hitting the wall’ / feeling of fatigue, dizziness and

hunger. This feeling can be partially

reversed by consuming some quick-to-absorb CHO, such as a sports drink or soft

confectionary.

If

your athlete does ‘hit the wall’ during training – get them to evaluate their

eating habits for the last 24 hours, as there is a good chance they did not

consume enough CHO.

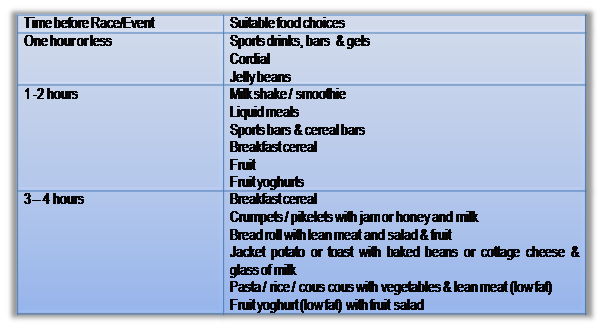

Re-fuelling before exercise

During the overnight fast glycogen stores are

depleted as energy is still burnt whilst sleeping. On awaking, glycogen stores

need to be refueled prior to training in order to provide an energy source.

This will improve performance during the session and also aids in recovery. It

is essential that athletes snack accordingly prior to early morning swim

sessions and when training schedules are busy.

Snacking around training and the timing of food around training maximises

performance and prevents athletes ‘hitting the wall’. A pre training snack 1-2 hours prior to

training is ideal. For early mornings, liquid meals such as smoothies or sports

drinks are better tolerated. Ideally, a meal is consumed 3-4 hours

prior to training or racing with a snack 1-2 hour prior. See post training and

competition snacks for examples of good food choices.

Recovery from Training

Athletes

can train up to twice a day, 6-7 days a week and as a result require a diet

both high in energy and high in CHO.

Athletes who fail to consume enough CHO will fail to recover adequately

between training sessions, resulting in fatigue, loss of body weight and poor

performance. Additional energy

requirements for growth may compound the problem. Athletes with high-energy

requirements need to increase the number of snacks during the day and make use

of energy-dense foods.

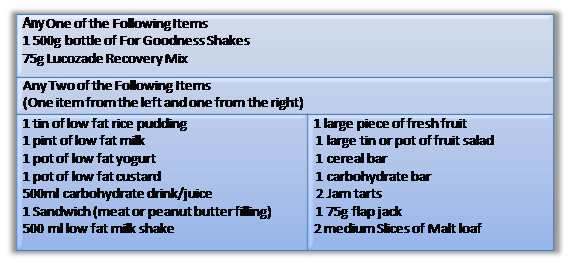

Immediate Post-Exercise Snacking

The timing and composition of post

exercise snacks and meals depends on the duration and intensity of the exercise

session (i.e. whether CHO stores were depleted) and when the next intense

workout will occur. After intense exercise sessions when muscle glycogen stores

are depleted the athlete should aim to consume 1g of carbohydrate per kg of

body mass immediately after exercise to replenish glycogen stores.

Protein consumed immediately after

exercise will provide amino acids for the building and repair of muscle

tissues. Consuming 10 -20g after exercise will be valuable after an intense

pool session and especially after an S&C session.

In the table below there are a number of

example foods which could be consumed immediately after sessions and stored at

the pool in lockers or in the fridge! This is not extra nutrition and should

make up part of an athlete’s daily energy intake. The examples shown are based

on a 70kg athlete and should be adjusted accordingly to suit the athletes’

nutritional requirements.

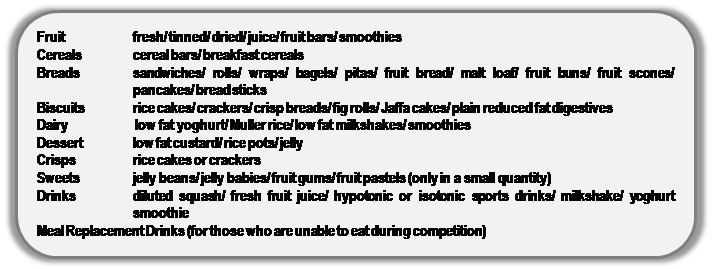

Competition Nutrition

Muscle glycogen stores can be filled by 24 hours of a high-CHO diet and rest. Athletes who are undertaking a long taper may need to reduce total energy intake to match their reduced workload, otherwise unwanted gains in body fat will occur. Fluid levels and CHO stores need to be replenished between events and between heats and finals. Athletes should drink a CHO-containing fluid such as a sports drink, fruit juice or cordial when there is only a short interval between races. Snacks such as yoghurt, fruit, cereal bars or sandwiches are suitable for longer gaps between races or for recovery at the end of a session. Between heats and evening final sessions, athletes should eat a high-CHO lunch and have a nap. On waking, a CHO-rich snack should be eaten before returning to the pool.

Making Good Food Choices in Competition & Refuelling

Competition schedules can be hectic and for athletes competing in multiple events, refuelling and rehydrating between races is essential to optimise performance. It can be difficult for athletes to know what to eat and drink between events depending on the time between races. Just as athletes train in the pool to adapt to training and competition nutrition strategies need to be adapted to by practising them in training and smaller competitions.

Equally important is being prepared; preparing ahead for food and hydration choices should be as much a part of an athlete’s preparation routine as packing towels, goggles and suits. Advance preparation for food and fluid intake throughout competition will prevent reliance on canteen foods which may be inappropriate recovery choices. Good nutrition during competition sets athletes up not only for their next race but also for a good night’s sleep and the next day’s racing. The table below provides some examples of suitable choices for between races during competition.

HYDRATION

Water is an essential part of an athlete’s diet. Mild dehydration is not harmful but severe dehydration can be to both health and performance. In warm/hot environments where athletes are likely to witness high sweat loss, it is recommended that they drink plenty of fluids beforehand.

Each individual will sweat different amounts, which also results in a loss of weight during exercise. The idea is to limit the weight loss to no more than 1-2% of the initial body weight. There is no standard sweat rate during exercise because sweat losses will vary depending on the weather conditions, exercise intensity, exercise duration and fitness level of each athlete. As a rough guide, Cox et al. (2002) found average sweat losses in swimmers to be 365ml/ hour in females and

415ml/ hour male. Athletes can develop their own hydration strategy to compensate for their own individual sweat losses. It is important that the athlete gets to know their body and understand when they need to be taking more fluids on board.

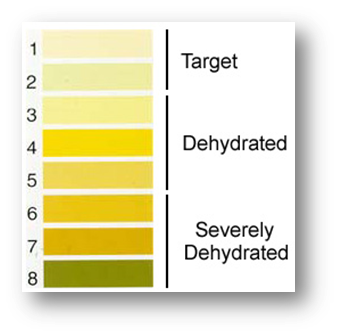

Monitoring Fluid

Loss

- Record body weight

before and after training:

1 kg loss in body weight is equivalent to 1 litre of sweat loss. Monitor fluid intake and record daily weight - Use the urine test:

- Look at urine colour (using the chart below), volume and frequency – the aim is for urine to be clear in colour, plentiful in volume, but frequency should not be to the extent where it continuously interrupts training sessions. If urine colour is dark and volume and frequency is sparse, then more fluids should be consumed.

Sweating not only involves the loss of water from the body but we also lose body salts such as sodium, chloride and potassium, often referred to as electrolytes. It is for this reason that sports drinks and other drinks containing carbohydrates and/or salts are generally more effective than plain water for replacing fluid lost through sweat. There is also some evidence to say that “salty” sweaters may be at a greater risk of muscle cramps and that this risk can be reduced by taking on drinks with more salt in them, or alternatively adding a pinch of salt to water/cordial that is usually consumed.

Drinking Strategies

Before Exercise: Ideally drink 500ml two hours prior to exercise and 125 – 250 ml immediately before to reduce the risk of dehydration. This may not be possible in early morning sessions. However athletes should ensure that some fluids are consumed, as the body will be dehydrated from the overnight fast whilst sleeping.

During Exercise: Athletes should try and drink at regular intervals during training to reduce dehydration. A rough guide for 125 – 200ml to be consumed every 15 minutes. Athletes need to be careful as it is possible to drink too much.

After Exercise: Fluid replacement should begin immediately after exercise; athletes should try to drink 600ml as soon as possible. Athletes should also try to keep sipping on fluids throughout the day in order to maintain the recommended ~ 2 of fluid outside of training.

2% loss in body weight before and after a session

Thirst (usually not the best indicator as can often already be dehydrated at this point)

Headache

Vomiting

Dizziness

Irritability

Decreased performance compared to ‘normal’

Cramps

Concentrated urine (dark yellow in color)

Nausea

Unusual fatigue

Loss of appetite

Poor concentration

What can coaches do?

Be aware that drinking during exercise does not come naturally to many athletes. It is a skill that needs to be developed and practiced just like their stroke.

Educate the athlete. Explain the importance of fluid intake whilst training so that they understand that it can have an effect on performance as sometimes they are not aware.

Optimise drinking opportunities throughout training i.e. between sets and where there is a longer rest period.

Monitor fluid balance periodically

Ensure athletes have access to chilled fluids which suit their taste preferences and requirements.

INADEQUATE NUTRITION AND THE EFFECTS WHILST SWIMMING

"I wasn't feeling well in the first half. I felt down, man. I had

three slices of pizza before the game and the food took me down."

Leroy Loggins, basketballer with the Brisbane

Bullets after 1986 semi-final

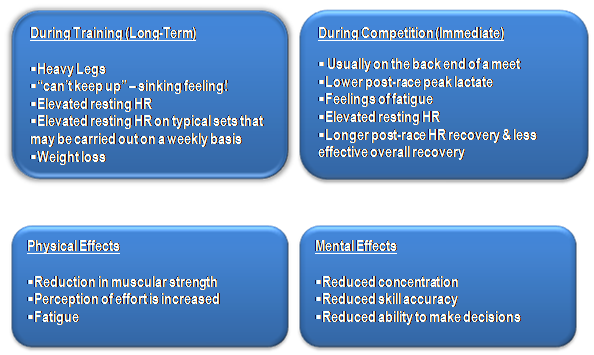

As highlighted, inadequate

nutrition can have potential negative effects on an athlete’s performance

whether it is in the water or on land.

So what are the signs that may indicate that an athlete may not be

consuming an adequate diet i.e. a diet insufficient in CHO?

Effects of Poor Nutrition on

Swimming Performance

Effects of Fluid Loss on Swimming Performance

Effects on immunity

Hard training increases the level of stress hormones and inflammatory proteins which compromises the body’s ability to fight infection. Immune cells have been shown to decrease temporarily in strenuous exercise of over 90 minutes in duration, further putting athletes at risk of infections such as bacteria and viruses which can cause common colds and the flu.

A varied diet is essential to provide all of the macro and micro nutrients required to protect from infection. Specifically, carbohydrate, protein, zinc, iron, magnesium, manganese, selenium, copper, vitamins A, C, B6 and B12 play essential roles in immune function. All are best gained from a diet high in fruit, vegetables, cereals and lean protein. Excessive amounts of these nutrients can be detrimental and supplementation is generally not required unless deficient or in special circumstances (limited food supply). Fuelling and recovery strategies aid in overcoming the detrimental effects of exercise on immunity.

Keeping hydrated also plays a part in immunity by maintaining the flow of saliva which contains anti-microbial proteins. Saliva flow can reduce throughout exercise and hence drinking at regular intervals can boost immune defence.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids may also potentially play a role in immunity due to their anti inflammatory effects. It is encouraged to include oily fish (salmon, tuna, sardines, mackerel & herring) around three times per week.

Probiotics are also recommended based on current evidence to support immunonutrition. Probiotics can increase the numbers of ‘good’ bacteria in the large intestine and are themselves live micro organisms. They can reduce the incidence of respiratory illness and gastrointestinal problems. Probiotic yoghurt with a high count of probiotics (Activa) is recommended for regular consumption.

Effects on Sleep

Sleep deprivation can cause increased depression, tension, confusion, fatigue and anger. Furthermore, decreased power in aerobic and anaerobic exercise may result from poor sleep. Adequate sleep is a vital component in an athlete’s recovery. Tryptophan (an essential amino acid) containing foods such as milk, meat, fish, poultry, eggs, beans, peanuts, cheese and leafy green vegetables can improve sleep quality.

High glycaemic

index meals have also been shown to improve sleep onset when taken four hours

before bed in comparison to a low GI meal and in comparison to when taken one

hour before bed. Caffeine and alcohol

should also be avoided due to the detrimental impact on sleep. Alcohol may affect

quality of sleep and caffeine with its stimulating properties should be avoided

in the hours before sleep and in large doses (Jeukendrup, 2010).

Sports Foods

Sports foods are developed to supply a specific formulation of energy and nutrients in a form that are easy to consume. They can play a valuable role in swimming in allowing athletes to meet their specific nutrition requirements when everyday foods are unavailable or impractical. This is usually immediately before, during or immediately after training/competitions.

Sports foods and BDS

Lucozade products are the only sports foods which British Disability athletes’ should use and they will be available at camps and competitions.

Example sports foods

Sports drinks (e.g. Lucozade Body Fuel) – These products can be used immediately before training sessions to increase blood sugar levels; during training to maintain blood sugar levels and hydration; and immediately after exercise to replenish muscle glycogen stores.

Recovery shakes (e.g. Lucozade Recovery Mix) – Such products can be used immediately after (within 15 minutes) of training to replenish glycogen stores and repair muscle damage caused by the training session and to promote protein synthesis.

Sports waters (e.g. Lucozade Hydro-active) – Sports waters aim to

replicate the content of the water lost from the body via sweat. Thus, these

products are particularly useful to maintain a hydrated state during training,

in hot environments and aboard planes when water and electrolyte losses are

increased. These are also low in

carbohydrates and energy, making them more appropriate for athletes on restricted

nutritional plans.

In terms of the

use of supplements please note that British Swimming has a NO SUPPLEMENT POLICY

and does not recommend any supplements.

Please refer to Chapter 16 for information on supplements and anti-doping

SUMMARY

- Athletes and coaches need to be aware of the importance that nutrition and hydration play when it comes to their performance in both training and competition.

Carbohydrate is the main fuel and energy substrate during intense training programmes and thus, needs to make up the main part of the athlete’s diet.

A varied diet improves nutrient intake and absorption by interactions between vitamins & minerals. Encourage athletes to consume a range of foods with brightly coloured fruit and vegetables.

Snacking around training is essential. A pre and post-training snack containing carbohydrates and protein needs to be prepared for in advance.

It is important to ensure athletes are well hydrated during prolonged exercise, especially in hot environments as a 2% decrease in initial body weight has been shown to have negative effects on performance.

Every athlete is unique. No two athletes will have the same nutritional demands or the same diet and hydration plan; therefore ensure that you do not compare athletes.

Coaches play an important part in role modelling and support for the athletes. Practise what you preach and athletes will feed from it.

REFERENCES

Australian Institute of Sport. Survival for the Fittest. NSW: Murdoch Magazines Pty Ltd; 1999.

AIS Sports Nutrition. Protein [Internet]. Canberra (Australia): Australian Sports Commission; c2009 [Updated 2009 Jun; cited 2010 Oct 1]. Available from http://www.ausport.gov.au/ais/nutrition/factsheets/basics/protein_-_how_much.

Burke.L.M, Maughan R.J & Coyle.E. Nutrition for Athletes: A Practical Guide for Eating for Health and Performance. International Olympic Committee; 2004.

Cox G.R, Broad E.M, Riley M.D & Burke L.M Body mass changes and voluntary fluid changes of elite level water polo players and swimmers. J. Sci & Med. 2002; 5 (3):183-193.

Jeukendrup A, editor. Sports Nutrition from Lab to Kitchen. UK: Meyer & Meyer Sport; 2010.

Maughan R.J & Burke L.M. Handbook of Sports Medicine: Sports Nutrition. Blackwell: An IOC Medical Commission Publication; 2002.

Stear. S. Fuelling Fitness for Sports Performance. British Olympic Association: 2004.

The University of Sydney. The Glycemic Index [Internet]. Sydney (Australia); c2009 [Updated 2010 Mar 25; Cited 2010 Oct 1]. Available from: www.glycemicindex.com.

Williams C. Diet and Sports Performance. In: Oxford Textbook of Sports Medicine. Harris M, Williams C, Stannish W, Micheli L (eds). Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996.

UK Sport www.uksport.gov.uk